Hip hinging is a very powerful movement that our bodies can do, that allows us to bend, lift, squat, and even climb up stairs and hills. Learning what a hip hinge is and how to do it well helps us to move more efficiently, minimize pain and injury, and enhance our fitness routine.

What is a hip hinge?

A hip hinge is essentially any movement that involves… well, hinging at the hips! Typically, it refers to a movement in the sagittal plane (forward and back plane) that allows the flexing at the hips (creasing the fronts of the hips), and subsequently extending the hips (opening the fronts of the hips). Rather than the movement being initiated at the spine, knees, or elsewhere, the movement pattern is initiated at the hips.

The hips are a ball and socket joint, as the joint is the union between the socket provided from the pelvis (acetabulum) and the ball from the thigh bone (head of the femur). So hip hinging must involve motion relative to the ball and socket, typically the socket of the pelvis rolling forward and back over the ball from the thigh bone.

Examples:

Many daily movement patterns, as well as exercises that one might perform, involve hip hinging. Here are some examples of hip hinging:

Sit to stand: The act of getting up and down from the chair involves hinging at the hips, as to sit, the hips must flex, and to stand, the hips must extend.

Deadlift: Lifting and lowering a weight from the ground using a hip hinge

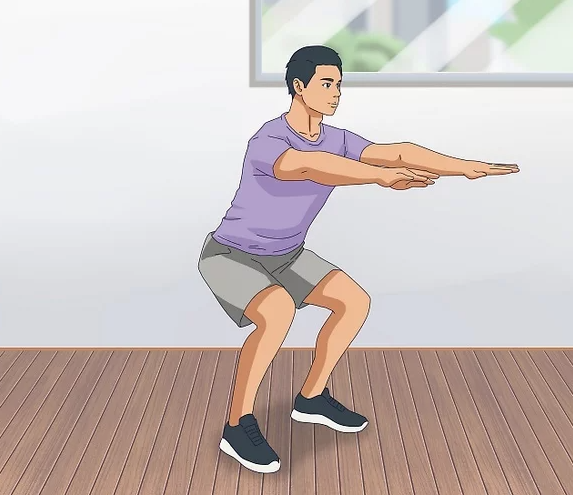

Squat: Sitting the hips back and down as knees bend, standing back up by thrusting hips up and forward

Step up: Single leg hip hinge involving putting one foot onto a step or platform which hinges the hip, and stepping up by extending through the hip/knee.

Kettlebell swing: Holding a kettlebell with both hands, hinging at the hips to send the kettlebell back and down, extending powerfully through the hips to send the kettlebell out in front

Sun salutations in yoga: A yoga practice is full of hip hinging. A traditional sun salutation, that involves going into a forward fold, lifting half way up, coming up to standing, etc involves a lot of hinging of the hips.

Why is it important?

Hip hinging uses the strongest, most powerful muscles in the body. This includes the gluteals, the hamstrings, the erector spinae, and the abdominals. Powerful coupling between these muscle groups helps create high levels of force, allowing us to move ourselves efficiently and lift heavy objects without injury. For this reason, getting to know how to hip hinge, and using hip hinges very often during daily activities and within a fitness regimen is an excellent way to stay strong and powerful.

Try these at home:

Here are several common cues that I use to teach people how to hip hinge-

“Buns in the oven”: Stand about 6 or so inches in front of a wall, facing away from the wall. Pretend the wall is an oven. Send your buns into the oven by sending your bottom back to touch the wall (hips go back, or hips are flexing, as your upper body leans forward. Once your bottom can feel the wall, pause. You are in a hinged position. Come back to standing by taking your buns out of the oven (hips go forward, hips are extending).

“Roll the roller”: Stand with a foam roller against your upper thighs. Roll the roller down your thighs by sending bottom back. Come back to starting position.

In kneeling: “Sit back towards your heels”: Knees on a kneeling pad, sit hips back towards heels as hands reach forward. Return to starting position.

Step ups: “Pull the thigh back”: Put one foot on a step or stool. Lean forward slightly. Step up, pulling the thigh back. Lower back down to starting position.

Written by Jacob Tyson, DPT - Physical Therapist, Yoga Instructor and The Wellness Station Team

Images:

https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/link/6e0531e00f714f43a2cb1f93fae0e762.aspx